ABC News

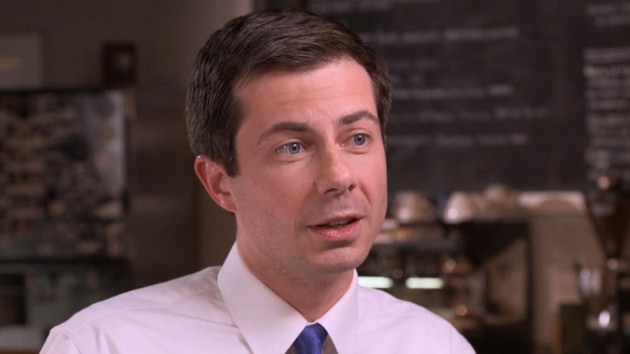

ABC News(WASHINGTON) — When Democratic presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg touted support from African American comedian and actor Keegan-Michael Key last week, his campaign was forced just hours later to clarify that the actor had not officially endorsed the former South Bend mayor, telling reporters he only sought to “encourage early voting and voter registration.”

Key appeared with Buttigieg on Saturday to drum up voter support at his Henderson, Nevada field office.

The gaffe did not attract much attention. However, it was not the first time the Buttigieg campaign overstated having a tie with a prominent African American figure, or black business.

In several instances reviewed by ABC News, the Buttigieg campaign identified people as supporters who later said their interactions had either been misunderstood or misconstrued.

The mix-ups have come at a crucial moment for Buttigieg’s campaign — which has made a concerted effort to promote his desire for inclusivity, even as polls show he faces an ongoing challenge finding support from voters of color.

Nationally, Buttigieg has support from 4% of Democratic and Democratic-leaning African-American voters, according to the latest Quinnipiac University poll released on Feb 10. That’s more than Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar and Hawaii Rep. Tulsi Gabbard, who poll at less than 1% with the same demographic of voters, but substantially less than candidates like former Vice President Joe Biden and former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who poll at 27% and 22% with Democratic and Democratic-leaning black voters, respectively.

A key test of that support is in South Carolina, which hosts its Democratic primary next week. Black voters there make up nearly 30% of the state’s population and more than 60% of the Democratic primary electorate.

The first indications there was confusion about some of Buttigieg’s claims of support came in October, when the campaign issued a press release in South Carolina that identified Rehoboth Baptist pastor and state Rep. Ivory Thigpen, and Johnnie Cordero, chairman of the Democratic Black Caucus, as prominent backers of the candidate’s “Douglass Plan for Black America.”

The comprehensive proposal, named after abolitionist leader and author Frederick Douglass, which aims to tackle racial inequality and improve the lives of black Americans, had support– just not an official endorsement from those politicians named in the headline of the release.

“I never endorsed the Douglass Plan and it’s not necessarily that it was a bad plan, but people have got to understand, you can’t talk for black people, we’re very capable of speaking for ourselves,” Cordero told ABC News, adding that he was given no explanation as to why or how the mix-up occurred.

Then last week, Buttigieg wrote an op-ed in a major South Carolina newspaper saying his campaign has “proudly partnered with local businesses,” citing Diane’s Kitchen in Chester and Atlantis Restaurant in Moncks Corner. But when ABC News reached out to the entrepreneurs about these new partnerships, they only remembered welcoming Buttigieg’s campaign as customers, not forging any sort of partnership with the candidate.

“I stand for what I stand for and I didn’t say I had a partnership,” Diane Cole, the owner of Diane’s Kitchen, told ABC News on Friday, Feb. 14.

After being asked by ABC News about Cole’s reaction, the campaign sent a series of messages to Cole trying to persuade her to change her position so it would more closely match the language Buttigieg used in his op-ed.

One version misspelled her name.

Cole told ABC News she rejected the initial requests, telling the campaign: “It sounds like you’re saying that I am your business partner. I’m only going to accept that you all stopped in while you were campaigning in South Carolina and I welcomed you all.”

The Democratic primary contender’s efforts to demonstrate a commitment to inclusivity and overcome his struggles to find support with voters of color has also included a promotional campaign in which he has touted support from well-known figures in the black community. Some of that support is genuine.

Buttigieg’s top African American surrogates include, Rep. Anthony Brown, Reggie Love — former body man to President Barack Obama — and Miss Black America Ryann Richardson.

Buttigieg’s campaign said the partnership language in the op-ed was intended to refer to efforts to frequent minority-owned businesses and that the candidate has been open about its efforts to seek a broad base of support for its initiatives, including the Douglass Plan.

“We’re proud to live our values as a campaign by holding events and spending money at Black-owned businesses in South Carolina and across the country, something we will continue to do throughout the campaign,” said Sean Savett, a campaign spokesman.

While there have occasionally been misunderstandings, campaign officials said there have been no attempts to overstate Buttigieg’s support from specific individuals or businesses. The language used on the campaign trail can be tough to calibrate, they said.

The campaign pointed out to ABC News, for instance, that Key’s choice of words introducing Buttigieg at a recent rally sounded very close to an endorsement.

“He’s left me so inspired and empowered that I came down here to Nevada to see all of you,” Key told the crowd, adding that Buttigieg “has actually inspired me, ladies and gentlemen.” What he had not done, Key later clarified, was give a formal endorsement.

The Douglass Plan press release

In October, the Buttigieg campaign released his “Douglass Plan”, and in a press release touted a headline from the HBCU Times saying that “More than 400 South Carolinians endorse Mayor Pete Buttigieg’s Douglass plan for black America.”

A backlash ensued almost immediately.

The online publication The Intercept was first to discover that three prominent African American state leaders in South Carolina — whose names were highlighted at the top of the campaign’s announcement — had said their position had been misinterpreted.

Columbia City Councilwoman Tameika Devine said though she has been asked by the campaign to review the plan she had not yet publicly weighed in. So, when she saw her name used to promote the plan, she was worried the press release may have created the misimpression that she endorsed the candidate since the word “endorse” was used.

She called the press release “intentionally vague” in an interview with The Intercept. She turned to social media to clarify her stance, tweeting, “Although I have not endorsed a candidate for President yet, I do support the Douglass Plan by Presidential Candidate @PeteButtigieg. This is a comprehensive plan to address economic inequities.”

Thigpen, the state representative, told ABC News that he considered the episode even more unsettling than Devine. Thigpen said he told the Buttigieg campaign he is a Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders surrogate when he was approached by the former South Bend, Indiana mayor’s campaign staffer to review the Douglass Plan and give his feedback. After reading the content of the plan, he agreed to commend the Buttigieg campaign for attempting to tackle such important issues as the wealth gap.

But he said he made it clear he could not publicly endorse the plan or the candidate.

“I thought using the word endorsement would be confusing,” Thigpen recalled, saying that he told the campaign he thought the plan was an important and positive step and would consider making a statement. Though he never sent one, he said a campaign staffer wrote him back requesting approval of quotes they had drafted on his behalf.

“They sent an email basically saying, if individuals want to opt-out of being listed as an endorser, then they needed to respond to the email by 4 p.m.,” Thigpen said of the message. “I didn’t see the email and so, of course, I didn’t respond to it. So they moved forward with my name.”

ABC News has seen a forwarded version of the email.

When the press release came out, Thigpen said he was stunned. He said the public affiliation with the Buttigieg campaign would directly conflict with his work on the Sanders campaign.

So he called and asked them to correct the release. He said the campaign was contrite, attributing it to a miscommunication.

“When it comes to politics and elections, and lending my name, whether it is issuing a quote of support or even an endorsement — that has value, obviously, or this wouldn’t have been a big deal,” Thigpen said.

After his name was removed from the press release about the plan’s support, the state lawmaker said he never heard from Buttigieg.

“I thought maybe some contact should have been made by the candidate,” Thigpen said. “I have not had the opportunity to speak him with in person, or over the phone.”

Cordero, the chairman of the Democratic Black Caucus, also was surprised to see his name on the release, even though he has an amicable relationship with Buttigieg.

The chairman recently endorsed Tom Steyer, but at the time of the incident he was not affiliated with any candidate and had been advising all the 2020 campaigns. So, when the campaign reached out to Cordero for a possible endorsement of the Douglass Plan, Cordero said he had been open to considering it but wanted to know whether African Americans helped to draft it. Cordero said the campaign never got back to him.

“I could not endorse the plan until those questions were answered and the reason is that — and I said this to (the campaign) — it is presumptuous for anyone to think they can develop a black agenda for Black America without talking to African Americans,” Cordero said.

After Cordero notified the campaign of the error, they removed his name from their list of endorsements. Cordero said he does not blame Buttigieg for the incident.

“I know that candidates are not always knowledgeable of what their campaigns are doing,” he said.

The campaign tells ABC News that of the eight people who authored the Douglass Plan, five were African American, one was of Asian American or Pacific Islander descent and two were white. The campaigns adds that the plan was reviewed by more than 40 black advocates, academics, and community leaders before its release.

Black business “partners”

Diane Cole, the owner of Diane’s Kitchen, said she remembers when a Buttigieg staffer asked her if they could hold a small meeting at her restaurant. Eight people including campaign surrogate Ryann Richardson, Miss Black America, met privately at her small black-owned restaurant in Chester, South Carolina, and spent about $90 on lunch.

To Cole, the campaign was simply another customer. But as South Carolina geared up for the first-in-the-South primary, Cole received a call from the Buttigieg campaign asking if they could mention publicly that they had visited her business. Cole said it was fine, but said she made it clear she did not agree to partnerships with the candidate, or his campaign.

One of the emails the campaign sent misspelled her name calling her “Diana”.

She said that she had never met or spoke with the South Bend Indiana mayor and as a voter she had been trying to decide between two other candidates — Biden and Bloomberg.

Then on Friday, she saw her name listed in Buttigieg’s op-ed — identifying her restaurant as a partner of his campaign.

Buttigieg campaign officials said they viewed the op-ed as a chance to promote the fact that they were frequenting minority-owned businesses — not that they had forged a formal relationship Cole’s restaurant.

Cole said she did not read it that way, and said she had not consented to the listing. But she brushed it off.

“It really doesn’t bother me, because I know the truth,” Cole said. “I don’t get mad. I don’t stress over stuff like that.”

The exchange that occurred after ABC News asked the Buttigieg campaign about the discrepancy only seemed to make matters worse, as Cole rejected a series of statements the campaign wanted her to release, emails Cole shared with ABC News show, including the one that misspelled her name.

After four attempts, the emails show they finally agreed on this: “Diane’s Kitchen greatly appreciates, Pete Buttigieg and his campaign for visiting and supporting my business. We are thankful for their willingness to choose Black owned businesses here in Chester, South Carolina.”

Another business Buttigieg identified in his op-ed as a partner was the Atlantis Restaurant and Lounge, the site where he held a campaign town hall with radio host and T.V. personality Charlemagne tha God on Jan 23.

Christian Dubois, who does public relations with Atlantis, said the restaurant did send a note to Buttigieg’s South Carolina press secretary in which they thanked the candidate for selecting the business for its January event.

“Atlantis restaurant was honored to be selected as the site to host Mayor Pete and Charlemagne for a much-needed conversation on why the next president must invest and not only black business but black people,” the note read.

Still, owner Wendell Varner said he never expected to be identified as being a partner of the Buttigieg campaign. Varner said he only learned of the newspaper mention when ABC News contacted him to verify his affiliation with the campaign.

“It’s a little disheartening to say that — that they would say that we have a partnership with them when we don’t,” Varner said. “We actually don’t support any presidential candidate and we try to stay out of politics as a business entity.”

After ABC News asked the Buttigieg campaign about the Atlantis statement, the campaign contacted ABC News to say the establishment had agreed to say publicly that they were “proud to partner with Mayor Pete in January.”

But the restaurant owner followed up with ABC News again, a few hours later, to make clear he was “not in any type of partnership with the Buttigieg campaign.” Varner said he would have allowed any campaign to visit.

“When you say ‘partner,’ in a sense they paid us to have an event at our restaurant,” Varner said.

Copyright © 2020, ABC Audio. All rights reserved.